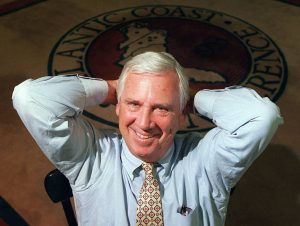

Part 3: ACC thrived under Corrigan’s leadership and vision

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third in a multi-part series about the life and times of the late Gene Corrigan, focusing on his work as athletic director at Virginia and Notre Dame, and as commissioner of the ACC.

By Jerry Ratcliffe

One of the most influential people in Gene Corrigan’s life was former ACC commissioner Bob James. James had taken a young Corrigan under his wing, perhaps having a notion that someday, just maybe Corrigan would sit in his seat.

When Corrigan left Virginia as athletic director for the same position at Notre Dame, he knew it would be difficult to see his old boss. James hated Notre Dame.

During his ninth year of 10 in South Bend, Corrigan was perfectly content. It was a family atmosphere, great place to work. It was different than Virginia.

“When I was at Virginia, I would go before the Board of Visitors three or four times a year and give a report on athletics,” Corrigan told Father Hesburgh, who along with Father Joyce, ruled Notre Dame with an iron hand for decades.

Hesbergh told Corrigan that he would not perform such a duty at Notre Dame.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute, I’m a big shot. Are you telling me I can’t report on the athletic department to our board?” Corrigan said.

“Father Hesbergh told me, ‘If I let you report to them, they’re going to think you work for them. You work for Joyce and me and the three of us will handle athletics here. We don’t need their help,’” Corrigan recalled.

Corrigan had just hired Lou Holtz to restore Notre Dame’s football program that year, which Holtz would do, going on to win a national championship in 1988. Unfortunately, Corrigan wouldn’t be there to enjoy the fruits of his labor.

In 1986, Georgia Tech athletic director Homer Rice had called Corrigan and said that Bob James was going to step down as commissioner, and that the ACC wanted to talk to Corrigan. The Notre Dame AD told Rice he didn’t think he wanted to do that, that he didn’t know anything about being a commissioner.

A year later, James died at the age of 66. At Notre Dame, Holtz had a pretty good season and had a great recruiting class coming in. Corrigan visited North Carolina for James’ services and Rice approached him again about becoming the commissioner. Once again, Corrigan said no.

Shortly after, family caused him to reconsider. Most of his children and grandchildren lived back East, and so Corrigan began to think hard about the situation. He went to the College Football Association meetings, and guess who he bumped into? Homer Rice.

“Homer came up and said, ‘One more time, will you talk with us?’” Corrigan said. “I said yes.

“It was the only job I ever took where I made more money than I did before. My wife said to me, ‘You’re the dumbest guy in the world.’”

Corrigan never took himself seriously, one of the reasons everyone loved him, and was always poking fun at himself.

The ACC had the press conference to introduce the new commissioner at the airport in Greensboro, and he always remembered that Bill Millsaps, the legendary sportswriter from Richmond, asked him about what his goals were for the conference.

“I told Bill that I didn’t have any goals, that I had to learn how to be a commissioner. I told Bill to call me in a year, and he did. He kept on me. It was so funny.”

Corrigan was 60 years old when he took the job, which he kept for a decade. Again, a great people person, a guy who had a touch for handling people, and always willing to listen, Corrigan became an immensely popular man in the job.

“I had a great group of ADs in the conference, Tom Butters, Homer Rice, John Swofford, Gene Hooks, Jim Kehoe, Dick Schultz,” Corrigan said.

He also had a terrific staff in Greensboro including Tom Mickle, who helped come up with the initial idea of a college football playoff with the Bowl Coalition, that led to the BCS, that led to the current playoffs.

“I learned a long time ago to hire smart people,” Corrigan said with a twinkle in his eyes. “They need to be smarter than you are. I loved being commissioner. I had so much fun.”

He carried over some of the same policies he had learned as an AD. He never closed the door to his office unless a student-athlete came in.

As an AD, he managed by walking around the building.

“I knew half the time [the coaches] were mad at me for something. I had been a coach, so I knew. If I could go in there every month or so, sit down and put my feet up and just talk, I think that made a difference.

“At the end of every year, each coach had an afternoon to talk to me about their dreams, hopes, where we had fallen short, and we could say to them where they had fallen short.”

Because of that background, he had a real sensitivity to the problems ADs had, which helped him rule as commissioner. Money, coaching changes, this and that. He believed his job was to stay in touch with all the ADs. He called them religiously every week to just ask what’s going on, or that he saw something in the papers. He also would visit each AD two or three times a year.

Corrigan did surround himself with smart people in the ACC office, including Fred Barakat, who oversaw basketball officials and ran the basketball tournament.

“People didn’t know how good he was,” Corrigan said. “In 10 years, I never had a coach call me and complain about officials…ever. Fred had been one of them, he had been a coach, and so coaches knew he was going to work for them.”

Corrigan was smart, too, and while he had an understanding and compassion for ADs and coaches, that didn’t mean he was a softie. He always had a strong, but common-sense way of handling problems.

“When I was at Notre Dame, I used to read the Chicago Tribune, which covered the Big Ten, and I always got the impression from coaches quoted that nobody ever lost a game, that the officials lost every game for them,” Corrigan said. “Father Hesbergh made it clear to us about coaches. If you cheat, you’re going to get fired. If you complain, you’re going to get fired. We keep our business here, we don’t share it with people.”

When Corrigan arrived to oversee the ACC, that first football season he didn’t like what he saw. All the coaches were chirping about officials.

Clemson had lost a tough game against Auburn, went to the Atlanta Touchdown Club for a speech and ripped the officials. Shortly afterward, the ADs had a conference meeting in Greensboro and Corrigan brought up the criticism of officials and said, “We can stop this pretty simply.”

He decided to write a letter to every coach in every sport and informed them that if they make complaints about any officials, they’re going to get suspended for a game. There would be no appeals. The ADs approved the measure, and the ACC office sent out the letters.

No sooner had the letters gone out that Corrigan had gotten home from a Maryland game and saw on the news that Duke had lost a close game against NC State due to a controversial call that would have reversed the outcome.

There on TV was none other than Duke coach Steve Spurrier, who said that he had played football all his life from little league to the pros and that the call was the worst he had ever seen.

“I said, ‘Oh my god, that’s my alma mater.’ I called Butters the next morning and said, ‘Did you see your boy last night?’ I asked Butters what he wanted to do, that I’ll come down the next morning, so have [Spurrier] in your office at 9. It’s better for me to tell him than for you to tell him.

“Spurrier was so competitive. Got there to the office and I told him what the new policy was and he said, ‘Huh?’ I said did you get my letter? He said what letter? I said don’t give me that.

“But…,” Spurrier interjected. “There are no buts, Steve, you’re suspended. You can be with your team until a half hour before the game but when they come out of the locker room, you’re out of the stadium. You can’t be in the press box.”

The ruling didn’t go down well.

“Spurrier said, ‘I want you to tell my team that I can’t coach them,’” Corrigan remembered.

Butters jumped in and added, “Hey, you broke the rule, Gene didn’t.”

It was a big game, Duke vs. Carolina. The Blue Devils beat the hell out of UNC. After that, Corrigan never had any issues with Spurrier and they developed a good relationship.

Other coaches would get the suspension, including Virginia’s George Welsh and Maryland’s Bobby Ross.

It wasn’t just football coaches that Corrigan had to deal with. There was an uprising between legendary Dean Smith at Carolina and newcomer Rick Barnes at Clemson.

They got into it big time in the tournament. Smith had complained of Barnes’ players — particularly a European player, Iker Iturbe — playing too physical. The squabble began during the regular season but boiled over into a heated argument that witnesses thought might lead to fisticuffs between the normally calm coaches in the tournament.

“Clemson wasn’t going anywhere but Carolina was going to the [NCAA Tournament], but there was equal guilt,” Corrigan said. “I waited until the summer and I called their ADs and said I wanted those two to come by my house the following Tuesday at 11 o’clock.

“They called back and said they can’t come. I said, ‘Fine, tell them they’re both suspended for the first two games next season. The ADs called back and said they’ll be there.”

Smith showed up first, and according to Corrigan must have had 30 film cases with him, his arms full, carrying him up to Corrigan’s house.

“I said, ‘Take them back to the car. That’s not what we’re here to talk about,’” Corrigan remembered. “Dean said, ‘People are trying to hurt my players.’ I said to Dean, ‘We’re talking about the way you two guys acted.’”

The three met for about an hour and a half, and when the coaches left, Corrigan informed them that he was going to bring this feud to an end right then and there and it won’t be talked about again.

“I’m going to issue a statement and you’re going to have statements in there where you both apologize for your actions. I had Mickle and Barakat work on the statement. I said it had to be good, fair and not humiliate anybody. At five o’clock we have it to the Associated Press. I got a call from Dean, who said he felt like he was saying more good things about Rick than Rick was saying about him.”

Corrigan chuckled after telling that story, remembering Smith.

“When I look back on what a great coach that guy was,” the Commish said. “People up here in Charlottesville hated that guy because he won. But his kids idolized him. He never used a curse word. When you think about that guy, he made his program the envy of everybody.”

One of the more exciting things about being “The Commish” was the ACC’s first expansion. When he took over the league, Penn State had left its independent status and joined the Big Ten. Corrigan believed that Penn State belonged in the ACC, but had no idea the Nittany Lions were ready to join a conference.

For the next five or six meetings, Corrigan would have Mickle or assistant Jon Lecrone or someone else play the role of a president of a college who was interested in joining the ACC. The ADs and presidents weren’t crazy about that process and said they weren’t interested in expansion.

Corrigan replied, ‘Hey, you didn’t pay me to sit still. This is what you’re going to get.’”

About a year later, Corrigan and the ADs were at Sedgefield Country Club, where the league was originally created. The Commish said before the meeting breaks up, he wanted each AD — under the assumption that the conference was going to expand — to mention a school they’d most like to take.

He expected at least four schools to be nominated. He got two: Florida State and Syracuse. The football guys wanted Florida State and the basketball guys wanted Syracuse. The ADs were as surprised as Corrigan that there were only two.

That showed some unity that had not been exhibited prior to that meeting.

“What do you want me to do with this?” Corrigan asked the ADs. “How about I call FSU and Syracuse and see if they’re interested?”

The Commish called Jake Crouthamel at Syracuse, and the AD responded that, ‘Oh man, we would love to do that but we can’t just leave the Big East. We’re one of the founders.’ He also suggested joining the ACC in everything but basketball and that the ACC woo Syracuse.

Corrigan told Crouthamel to forget he called because, “That ain’t going to happen. They’re not going to woo anybody.”

He called Bob Goin at FSU.

“I’ll never forget what he said: ‘I’ve been praying that you would call. We’ve had this thing about being considered for the SEC. This is my dream, that we’d get in the ACC.’

“I said, ‘You’re kidding?’ Goin said no.”

Corrigan sat down with his trusty friend Mickle and said this had to be handled just right, that a faculty rep and AD from each school had to come in, that we would have FSU’s president and Goin and provost to come up and meet.

Meanwhile, Corrigan told Goin that when the FSU delegation came to the meeting, they shouldn’t talk about athletics.

“We knew about that already. Those people wanted to know what kind of school FSU was. Make a report, and it will either fly or it won’t,” Corrigan said. “They did a good job.”

When the meeting ended, Virginia’s D. Alan Williams, faculty rep, and the faculty rep from Duke both told him that FSU was a better school than they had thought.

“I got in the car and drove from Maryland all the way down and talked to every president, AD and faculty rep before we took a vote,” Corrigan said. “Everybody was on board except Duke. Butters was adamant against it. Eight was enough, he just wasn’t a football guy.”

There was an 8-p.m. vote. Clemson was a yes, so was Georgia Tech. Duke was an expected no. Then came a surprise — Maryland was a no.

“No?” Corrigan said. “When I left up there, it was a yes. What was this all about?”

Carolina then abstained. NC State stuck with Carolina for political reasons and also abstained. Virginia was a yes, Wake was a yes, so the vote was 4-2-2. Corrigan needed six votes.

He had a conference call with each AD immediately after the vote. Swofford had no idea what his president at UNC was going to do. Corrigan was flabbergasted.

He found out that Andy Geiger at Maryland said it was going to cost him $60,000 a year more to send athletic teams to Florida, to which Corrigan answered, “Andy, we’re talking about millions of dollars here.”

Eventually he got a unanimous vote from the ADs, Florida State came in, and six weeks later the ACC struck a TV deal that jumped the league’s football contract from $3 million a year to $17 million.

“That took us to where we had never been before. Previously, we had no presence in the largest state in our territory. Does that make any sense?” Corrigan said upon review.

He would have taken Georgia and Florida, too, but they didn’t want to leave the SEC.

Another one of his goals, that he could have told Millsaps about later, was convincing the ACC members to have equal sharing of the money.

“Florida State would have been taking probably 75 percent of the money from television and the bowls, but FSU never complained about one thing. We told them all the bad stuff early. It was a huge thing for the schools, worth $2 million to every school in the conference.”

His era of the ACC was a great one, and like Corrigan said, he had a lot of fun.

“How lucky was I to have worked for Washington & Lee, Virginia, Notre Dame and the ACC?” Corrigan said.

How lucky was W&L, UVA, Notre Dame, and the ACC that Corrigan came their way? For all of us who had the privilege of knowing a man like that who rarely comes our way, how lucky were we all?