Football Legends Share Stories At George Welsh Memorial

By Jerry Ratcliffe

All photos courtesy Jim Daves, UVA Media Relations

Bronco Mendenhall walked into John Paul Jones Arena on Saturday morning as a scheduled speaker for the George Welsh Celebration of Life ceremony. He quickly became just as mesmerized as the rest of us by the array of legend in attendance.

“I walk in and Franco Harris is speaking,” Mendenhall told the Virginia press corps a few hours later after closing spring football with a team scrimmage at nearby Scott Stadium. “That’s an amazing thing when you see Hall of Fame players coached by our coach.

“You just look around, all the names of coaches and players whom [Welsh] impacted, what they all went on to do, that was significant to me and humbling,” Mendenhall said. “Without that experience today, I don’t think I would have had as clear a vision of what Coach Welsh did and what UVA football has been, and what that era looked like. That was really helpful to me.”

Mendenhall’s charge is to return Virginia football to the glory days of Welsh, who became the school’s winningest coach over a 19-year span. Welsh put UVA on the map after inheriting a program that experienced only two winning seasons in the previous 29 years of his arrival in 1982. Welsh passed unexpectedly on Jan. 2 of this year, 19 years after his retirement from coaching.

When Welsh hung up his whistle after the 2000 season, he retired as the winning coach in Virginia, Navy, and ACC history.

Saturday’s tribute was a two-hour-plus event, with all three schools he coached at represented: Penn State, Navy, and Virginia.

Hall of Famers, All-Americans, household football names from all three institutions and beyond, including a bevy of former NFL players, were scattered throughout the audience. Among them was Franco Harris, a running back Welsh recruited and coached at Penn State before Harris went on to become a legend with the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers.

Harris became one of the game’s all-time great running backs and his notoriety grew with his involvement in “The Immaculate Reception,” a freakish tipped catch by Harris from Terry Bradshaw that allowed the Steelers to upset the Oakland Raiders in a 1972 playoff game. Harris went on to become a Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee, and was in Charlottesville to honor Welsh.

Also on hand were two other star Penn State running backs recruited and coached by Welsh: Lydell Mitchell and Charlie Pittman.

Following is a roundup of what was said about Welsh by myriad of former players, coaches, and family members at Saturday’s tribute:

A Nittany Lion

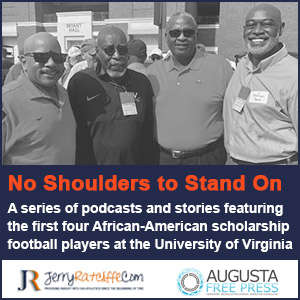

From left: Penn State greats Lydell Mitchell, Charlie Pittman and Franco Harris.

As Harris, Mitchell and Pittman, all stars at Penn State and later in the NFL, rose to approach the podium, former Georgia Tech-Alabama-Kentucky head football coach Bill Curry leaned over and whispered to event master of ceremonies author John Feinstein, “how’s that for a backfield.”

Indeed.

“George was our position coach at Penn State,” Harris said. “From recruiting and coaching all three of us and sending all three of us to the NFL changed everything for us and changed everything for me and prepared me for what was to come.

Harris said he felt like all the players and coaches that served Welsh from all three schools were one family.

“George would take the time to shake every player’s hand before every game,” Harris said. “How special was that? He was a good man and a great coach.”

Mitchell told a story about his recruitment by Welsh, who when looking for the running back prospect, Welsh was told he could find Mitchell at the local pool room. Welsh found Mitchell there shooting pool, sat and watched without saying a word. Finally Mitchell asked the coach if he wanted to go to a nearby bowling alley and grab a burger, then went back and shot more pool.

“George was quiet the whole time,” Mitchell said. “I thought George didn’t talk.”

The two bonded over time, but it took time as Welsh rarely opened up to anyone.

Pittman, who grew up in the inner city of Baltimore, said he was a shy kid and it was Welsh’s job to convince him to come to Penn State and play for a coach no one had ever heard of, Joe Paterno, who had just been elevated to head coach.

“The decision to allow George Welsh to enter my life and send me to Penn State, gave me life lessons I’ll never forget,” Pittman said. “Self confidence, I learned those lessons under Welsh and Paterno.

The Naval Academy

Ex-Navy kicker and former UVA grad assistant Bob Tata Jr.

Bob Tata Jr. left Annapolis with 19 of the program’s kicking records, none of which still stand as he comedically pointed out. He was once thrown out of one of Welsh’s Navy practices because “apparently you’re not supposed to learn how to juggle footballs on the sideline.”

Welsh was a no-nonsense coach and Tata was one of many players at all three schools that at some time during their career were tossed out of practice.

Tata pointed out a commonality of Welsh’s team uniforms at Navy, then Virginia, in that there was no school name on the front and no player name on the back, something Tata figured Welsh took from Penn State at the time. Eventually, Welsh was convinced to add both at UVA.

In honor of the late coach, Tata presented a Navy jersey to the Welsh family, with “Navy” emblazoned on the front and “Welsh” on the back. Welsh had been a star quarterback at Navy and finished third in the Heisman balloting. As Feinstein aptly pointed out, “George was Roger Staubach before Roger Staubach.”

Tata also recognized Navy star Chet Moeller, also a member of the College Football Hall of Fame, in the audience.

“George owned a meticulous attention to detail and had a brilliant football mind,” Tata said. “He wasn’t a big man, but you respected him. He was a teddy bear but people feared him. When I was a graduate assistant (at UVA), we were in a team meeting, and when George began to talk, somebody coughed, and George paused. When he started to speak again, someone else coughed.

“George got that look in his eyes and said that the next person that coughs is out of here,” Tata said. “Well, until he said that, I was fine. But suddenly there was a tickle in my throat and I was terrified I was going to be thrown out of there.”

Tata said he was speaking on the phone one day to a former Virginia player and they both remembered Welsh having a photographic memory. The former Wahoo told Tata, the next time he spoke to Welsh, ask him this question: how gratifying was it after giving up an 18-point lead, to watch Pete Allen return a kickoff to beat Georgia in the Peach Bowl.

Tata tested Welsh and the old coach didn’t flinch.

“One of the most amazing things about that return was Terrence Wilkins’ block on the edge to spring the play,” Welsh shot back to Tata’s amazement. “It was the first time Wilkins ever blocked anyone. Knocked the guy clear off the field.”

The Virginia Era

Longtime UVA assistant Tom O’Brien provides insight into Welsh’s brilliance.

Tom O’Brien, who was an assistant under Welsh at Navy and Virginia before going on to become head coach at Boston College and N.C. State, spoke on behalf of Welsh’s 19-year run in Charlottesville.

O’Brien said that his first exposure to Welsh was in 1975. He was performing a menial task that suddenly became an unforgettable moment.

“George used to carry a No. 2 pencil between his fingers, and I botched the task assigned me, to which George slammed his hand down and snapped the pencil and gave me that look, saying ‘I’ve got another blanking marine on my staff.’ From that point, I told myself that I’m never going to let that happen again.”

When he and most of the Navy staff followed Welsh to UVA in ‘82, Welsh’s wife, Sandra, called them the “Kiddie Corps.” Tom Sherman was the oldest at 35. Bob Petchel was 29. O’Brien was young too, like the whole staff.

“Virginia had won 33 conference games in 29 years … that’s what we were walking into,” O’Brien said. “George coached everything. Offense, defense, special teams. He used to carry around a notepad and a golf pencil and was constantly writing things down, things he would bring up the next morning in meetings about what we were going to do that day.”

O’Brien was correct. Welsh called the shots on everything and didn’t have an official offensive coordinator until he gave that title to O’Brien years later, to which O’Brien cracked: “I was with him 16 years before I was named coordinator. I said it was like getting my driver’s license.”

Not long afterward, O’Brien was named head coach at Boston College.

Two of O’Brien’s favorite memories of Welsh’s Virginia teams were the Peach Bowl celebration in ‘84, after the Cavaliers upset Purdue in the school’s first-ever bowl game; and beating Penn State in Happy Valley in 1989.

“After beating Purdue, when we went back to the team hotel, which had a big atrium, about 12 stories, and a fountain in the middle of the lobby, the Pep Band was positioned on the fountain playing our fight song when the team came in. People were everywhere and cheering, letting out their years of [football] frustration. I will never forget that as long as I live.”

O’Brien’s other favorite memory was 1989, the only 10-win season in school history.

“We were crushed by Notre Dame (Kickoff Classic at the Meadowlands) to open the season. George didn’t panic. At halftime, George said we’re going to use the second half as practice. Take the game plan and throw it out the window. We’re going to run our base offense and our base defense.”

UVA played better in the second half but was never really in the game. However, it helped the team improve nonetheless.

“The next game, we’re at Penn State. Now who in the world schedules Notre Dame (defending national champion) and Penn State away from home, back-to-back, to open the season?” O’Brien chuckled. “Shawn and Herman Moore reinvented the ‘alley-oop’ play, and we won.”

O’Brien went on to talk about how the next season UVA’s skilled players finally looked like Clemson’s skilled players, then discussed the ‘95 season when the Cavaliers lost heartbreakers at Michigan and Texas before becoming the first ACC team to hand Florida State a conference loss.

Before he finished, O’Brien also introduced another College Football Hall of Famer in the audience, UVA’s Jim Dombrowski, who went on to become a longtime starting offensive lineman for the New Orleans Saints.

Leaving a Legacy: Bronco

UVA coach Bronco Mendenhall inspired by Welsh’s standards.

Mendenhall said he used to see Welsh in the football offices’ break room, where the old coach would come by each morning and enjoy coffee while reading newspapers.

“He’d say, ‘How’s it going?’” Mendenhall said. “And I would ask him how he thought it was going.’ He would say, ‘You need players,’ or, ‘You need facilities.’ He was helping navigate a new coach. I feel like I’m a steward of his program and that matters to me.”

The current Virginia coach, now in his fourth year at the helm, said that Jim Daves, the school’s assistant AD for media relations, presented him with these oddities the other day.

When Mendenhall left BYU to become Virginia’s new head coach, he was 49 years old. When Welsh left Navy to take over at UVA, he was 49.

When Welsh arrived, the Cavaliers had experienced five losing seasons in the previous six years. When Mendenhall arrived, it was the same.

“I brought seven of my assistants here from BYU,” Mendenhall said. “George brought six from Navy.”

Welsh’s first year at UVA, the Cavaliers won two games, then six games the second year, then eight the third year. Mendenhall’s first year at UVA, the Cavaliers won two games, six games the second year, eight the third.

“Not only do I go into his facility (UVA’s Welsh indoor practice stadium), but I see his mural up on the wall,” Mendenhall said. “He set a standard and I’m responsible for that standard, which is daunting but possible because he proved it. We are trying to return to that.”

The Players’ Perspective

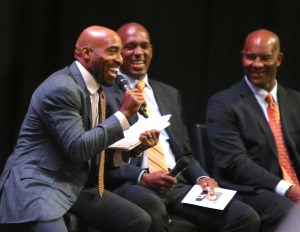

Ronde Barber, Anthony Poindexter and Chris Slade share a story about Coach Welsh.

(UVA’s Ronde Barber, Nick Merrick, Sean Scott, Shawn Moore, Anthony Poindexter, and Chris Slade)

RONDE BARBER (Best Cornerback in UVA history, stellar 16-year career with Tampa Bay Bucs):

“Danny Wilmer recruited me, but when George showed up at my high school (Cave Spring), I thought it was a big deal. I saw him sitting in the office and it was an indelible moment for me. He was the first head football coach to show up at my high school.”

Barber also did a great Welsh impression and said that in 1993, UVA had redshirted his twin, Tiki, and approached Ronde about redshirting as well.

“I went to his office and George said, ‘You’re not ready.’ I said, ‘OK coach, I’ll take a redshirt year.’ Years later, I walked into George’s office and told him I was ready to go to the NFL a year early. I got the same response, ‘You’re not ready … Christ, Ronde, you need another year.’ Well, George was right. I would have benefitted from remaining here another year.”

Barber said that Welsh was the embodiment of a leader. He was quiet, stoic, and people were somewhat scared of him. “But what he did to turn this program around was special. He created a culture of high expectations. I became a great pro, and later in life George became a friend that I relished seeing. His legacy is big.”

ANTHONY POINDEXTER (Legendary free safety and one of the most fierce hitters to ever suit up for UVA. Severe knee injury during his senior season impaired his NFL career. Is now defensive coordinator at Purdue):

“I always feared Coach Welsh, but in a respectful way. I was scared to go his office, and so I was terrified when I was named captain, because I had to go to his office. I told myself, ‘I ain’t going in there.’ But when I came back and started coaching (Poindexter began his coaching career at UVA), I saw the real Coach Welsh. I would say to myself, ‘Who is this guy with the 30-minute conversations? Who is this guy?”

Poindexter had the opportunity to leave UVA and turn pro a year early, and so when he made the decision to return for his senior year, he worked up enough confidence to go into Welsh’s office.

“I told him that I had decided to come back to school. Coach I’m going to come back and play for you. Coach said, ‘That’s great, but son you need to do what you need to do. If you go, I understand. Make this decision based on you.’ I didn’t know that [Welsh] had that side to him, that he really cared about me and my family. Quite frankly, I think he was telling me to leave.

“But I came back because I enjoyed college and my teammates,” Poindexter said.

He suffered a season-ending knee injury that final season against NC State, an injury that plagued his NFL career.

“I probably learned more from getting injured than playing for years in the league,” Poindexter said. “The ‘98 season, I got back on my feet (with crutches) and Coach allowed me to go on the road and remain team captain, to still be a part of the team and have a leadership role. I was on crutches and had a cast, but he knew it was important to me. He really did have a sentimental side to him. He treated me like a son.”

SHAWN MOORE (Arguably the best quarterback in VIrginia history, who led the Cavaliers to its only 10-win season, and the next season a national No. 1 ranking, while smashing most of the school’s offensive records):

“In ‘86, George wanted to redshirt that entire class. It was a pretty good class, a lot of good in-state players. The first game of the year we played South Carolina and beat the brakes off of them. We figured, we’re on our way, we’re going to win the national championship. Then we went on to lose eight games, so we figured maybe it was better that we were all redshirted. But we played in ‘87, ‘88, ‘89, and ‘90 and we were the first class to really get it started.”

Barber asked Moore how Welsh managed to turn around a program that had been the laughing stock of college football into the No. 1 team in the nation in less than 10 years.

“George was a great evaluator of talent. He had several assistants that went on to become head coaches. Some of the best conversations I had with Coach Welsh was after I came back to coach and we would be in the lunchroom talking. Before that, you really didn’t get to know Coach. I got to know the real man.”

Moore said that he believed he had a unique bond with Welsh, partly because he was the team’s quarterback.

“George always treated me different,” Moore said.

However, Welsh might sometimes have a different form of justice depending on who the culprit might be, as in the Citrus Bowl one year when a few of the players went out after curfew and got caught. One of those players was star receiver Herman Moore. On game day, Herman was on the exercise bike getting loose, and Shawn remembered Welsh saying to the guilty parties, ‘Look, I’m going to treat you all fair, but not evenly.’ Herman was off the hook.

CHRIS SLADE (One of the great all-time UVA pass rushers. Still holds the program record for sacks. Went on to a fabulous career with the New England Patriots. Now coaching high school football in Atlanta):

“Like most guys that played for Coach Welsh, you don’t get to know him when you play for him. As time went on, I reflected back on him, the life lessons, how to be a man, what I learned from him. Three years ago when we won the state championship, I received a handwritten letter from Coach Welsh, congratulating us on winning. I still have that letter on my desk. He was tough, but he had another side to him.”

Welsh rubbed off more on Slade than he would have ever thought while playing under the Hall of Famer. Slade remembers Welsh always saying, “If you’re on time, you’re late.” He learned about how to structure practices, how to get through each practice period and tons of other things about coaching that he has applied to his job.

Then there were those back-to-back losses to Georgia Tech in 1990 and ‘91, both on late Scott Sisson field goals. Slade remembered being in the visitors’ locker room at Bobby Dodd Stadium in Atlanta, a somber place that night, so quiet that you could hear a pin drop.

“Our athletic director Jim Copeland was standing in the back talking to someone, was a little too loud and laughing,” Slade remembered. “All of a sudden, George says, ‘Jim, what’s so funny?’ The AD said nothing was funny, to which George snapped back, ‘I saw you, you were laughing.’”

Slade said, “I was just sitting there with my head down, thinking, ‘That’s our AD.’ I guess when George meant silence, he meant silence. Nobody broke that rule.”

Shawn Moore, Sean Scott and Nick Merrick talk about their careers under Welsh.

SEAN SCOTT (All-ACC Defensive End in 1987 and a solid pass rusher. He didn’t play in the NFL but said that lessons learned from Welsh helped him through a 25-year career as a police officer and SWAT team leader. He now teaches criminal justice):

“I had a brother (football player) who had just graduated from Clemson, and I thought to myself we’re going to change some things here. I drank the Kool-Aid. I figured maybe we could change history. My whole class felt that way. We just felt like this was an opportunity to do something special, so I can relate to what Coach Mendenhall is thinking today.”

Scott said as a true freshman, first day of pads, he was excited to get started. Welsh was observing from the tower during a punt drill. Scott broke through the protection, laid himself out and took out the punter’s legs.

“Coach comes running from the tower and he wasn’t happy. I had never seen a grown man act that way. He was in my face. It was an awakening,” Scott said. “I was mad at myself. I said, ‘That’ll never happen again.’ Next play, I lay out, and I do it again. Took the punters legs out. I won’t go with the language, but Coach threw me off the field. I believe the quote was, ‘You’ll never play again.’”

Being a freshman, Scott was worried that maybe he had lost his scholarship or something, but in the opening game of the season (‘84), Clemson was tearing UVA up at halftime. Welsh decided at the half to start Scott at end and he played the entire half. UVA got hammered, 55-0, but the next day, Welsh told him that he had earned the defensive end spot as a true freshman.

“Without story one, story two would have never happened. It was humbling.”

NICK MERRICK (was in the program before Welsh arrived and spoke of the transition from a 1-10 season in 1981 to a Peach Bowl victory in ‘84):

“When Coach Welsh showed up, it was shock and awe. I think he knew it would take time. We were in awe of the discipline and the approach. There was a good mix of the talent that was there that needed to be developed.”

Merrick said that he envies today’s UVA players. Today they receive great swag in terms of equipment, etc., and have dining facilities, and get to play on real grass.

“We had meal tickets and ate mostly at a Shoney’s,” Merrick said. “Virginia plays on grass. We played on a concrete field painted green.”

UVA’s players would get the wrath of George from time to time those first couple of years when he told them they were “a bad football team.”

“But that second year, we did beat Carolina late in the season and finished 6-5, so we were making progress,” recalled Merrick. “There was some great new talent being brought into the program, and that moment in Atlanta, when we won the Peach Bowl, that was the perfect moment. It wasn’t winning the national championship, but it felt like it.”

Merrick said he was never totally sure during his playing days that Welsh knew his first name.

“I usually heard, ‘Merrick … Christ …’ and ‘You’re slow,’ all in the same sentence. But years ago, I had my son with me, a high school quarterback, and Coach talked to him and told him some positive things about me. It was really a gift and a total act of kindness.”

The Coach — Bill Curry, Sr.

Coach Bill Curry feared Welsh as a rival at Georgia Tech.

Curry, who played for the Green Bay Packers and Baltimore Colts, then was head coach at Georgia Tech (where he coached against George at Navy and UVA), then Alabama, Kentucky, and Georgia State, sent two children to UVA, Kristen, and son Billy Jr., who was UVA’s long-snapper for 47 consecutive games.

“At Georgia Tech, I’d be looking across the field and seeing that funny hat, sideways, and those glaring eyes,” Curry said of facing Welsh. “I hate to look across the field and see George Welsh because I knew he was smarter than me. I knew he could beat us with his brain.”

Curry said it was his duty, his task to try to get Welsh to throw that hat down, a habit of Welsh’s when things went awry, as many times as possible.

In 1985, when Curry had his best Georgia Tech team, he said his Yellow Jackets got hammered by Welsh.

“We only lost two games that year. We lost to Barry Word, Jim Dombrowski and Virginia in one, and the other was to Bo Jackson (and Auburn),” Curry said.

Curry wasn’t easily intimidated. He played for Vince Lombardi and Don Shula. He snapped the ball to Bart Starr and Johnny Unitas. But it was a little intimidating to face Welsh.

“He walks up to me before that game in ‘85, it was the obligatory handshake before the game. Those steely eyes coming from one of the greatest competitors that ever lived, and he comes up and says, ‘You have a freshman daughter at UVA. Tell Kristen to give us a call. She’ll be welcome to come to our house any time,’” Curry said.

“That’s not what I expected at all. He knows my daughter’s name? What is he trying to do, soften me up before the game?”

Lots of thoughts ran through Curry’s head.

Eventually, Kristen would visit the Welsh’s quite often and the families became great friends, a relationship that grew even more when Bill Jr., Billy, came to UVA.

“A few years later, I was at Alabama. Billy says, ‘I’m going to walk on at Alabama and work for you,’ and his momma said from another room, ‘Not a chance. If UVA will have you, that’s where you’re going.’”

Curry called Welsh and Welsh said he’d take a look at the long-snapper candidate.

“Billy spent five of the best years of his life under George Welsh and it was life-changing for him.”

Curry’s favorite story about Welsh was about when George invited the Curry’s to Nantucket on vacation. The Welsh’s had a second home there. It so happened that the late John Havlicek was holding a fishing tournament, so the two coaches were invited.

“We’re out on a boat, and I’m impressed to be on a boat with a naval officer (Welsh), and we’re out for about half an hour and George says, ‘We’ve got to take me back. I’m sea sick,’” Curry remembered.

“Sea sick? We’ve got to take you back to shore because you’re sea sick? But you were in the Navy. You were a naval officer. Sea sick?,” Curry said.

The boat returned to shore and dropped off the coaches. Welsh left the boat and muttered, “‘This is all Bill Curry’s fault.’ How he came up with that, I don’t know, but as he walked off, I noticed a little puck of a smile in the corner of his mouth.”

Family

George Welsh’s children receive ovation from those in attendance.

All four of George’s children were in attendance, Kate, Duffy, Matt, and Adam. Their mother, Sandra, passed four years ago. Their godmother, Sue Paterno, the widow of Penn State coach Joe Paterno, was in attendance, accompanied by her son, Jay Paterno.

Adam thanked the players for tolerating his dad’s coaching methods, which “could be interpreted at times for lacking in grace,” he joked. “And thank you for tolerating the expletives on the practice field.”

Kate said that her dad taught her self confidence, self esteem and a strong belief that she could do anything if she worked hard, believed in herself and never gave up.

She spent the last three-and-a-half months with George before his unexpected passing, and watched bowl games with him all day long on Jan. 1.

“We watched every bowl game together that day and nothing was wrong,” she said. “He was coaching until the end. He suffered a catastrophic stroke and was gone the next evening.”

Welsh was 85.

Kate said she learned a lot of things about her dad during that span, that he was a huge Red Sox fan but believed if he watched the games live, they would lose. She would leave him a note the next morning with the score, and he would sometimes watch the recording.

Welsh was also a huge reader, consuming two to three novels a week, and loved John Grisham’s work.

George told her that, “’God meant for me to coach football.’”

“He was a simple man but with a lot of complexity,” Kate Welsh said. “He was no-nonsense, but had a heart of gold.”

The celebration was closed with a full military tribute to the old salt, who suffered from sea sickness.

Fair winds and following seas ….