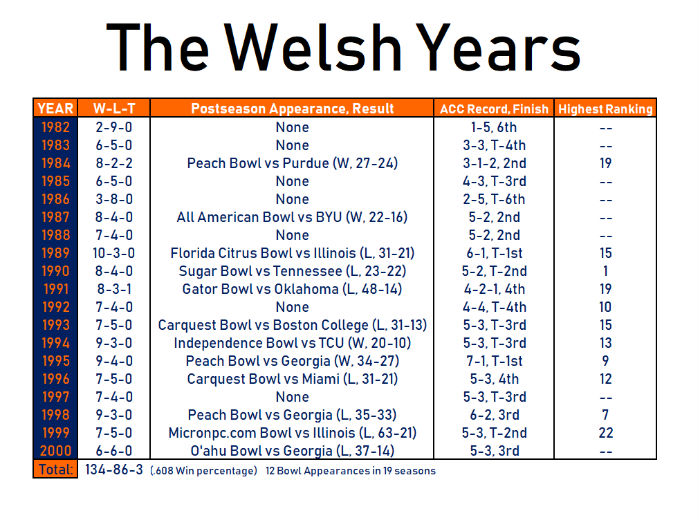

George Welsh: Building a Program

(EDITOR’s NOTE: When I researched for my book, The Virginia Football Vault … a history of the Cavaliers, I had the enjoyment of sitting down with Hall of Fame coach George Welsh for several days and just talk Wahoo football. Because there was a limited space for the Welsh era in the book, I had tons of leftover material, much of which had never been written. I’m bringing all that to you Wahoos in a series of stories about how George put UVa football on the map. This is Part 1. Enjoy.)

By Jerry Ratcliffe

George Welsh believed he could win at Virginia when he arrived on the scene in December of 1981. He had recruited similar players to Navy and won against somewhat similar competition.

Still, after Welsh arrived on UVa’s campus after Navy’s close loss to Ohio State in the Liberty Bowl later that month, he realized that rebuilding the Cavaliers might be a more challenging task than he had imagined. Virginia had experienced only two winning seasons in the previous 29 and was generally considered if not the worst, certainly one of the worst programs in college football.

“I just got here and had no idea that things were so bad,” Welsh said. “I was surprised with the facilities. I never took a tour (during the interview process), so when I saw the facilities I knew we had a problem.”

The first thing UVa’s new head coach did after recruiting was over in early February was to go visit the athletic director who hired him, Dick Schultz. It was smart on Schultz’s part to not give Welsh a tour of facilities when he was trying to lure him to Charlottesville. The coaches offices in University Hall were cramped and outdated, to the point that Welsh finally moved some of the staff to double-wide trailers behind U-Hall. Scott Stadium was small but quaint. Weight rooms, meeting rooms, etc., were antiquated.

Welsh went to Schultz and told him he thought he could get things done but that facilities were going to hinder the process. Welsh had faith he could take care of the football part if Schultz would take care of the rest and believed Schultz was the right AD to help get UVa football going in the right direction.

The former Navy coach and former Navy quarterback (Welsh finished third in the Heisman Trophy race his senior year at the Academy) had two things going for him at Virginia, though. He managed to bring the majority of his staff with him from Annapolis, and he inherited a number of strong players from his predecessor at UVa, Coach Dick Bestwick.

A lot of it was just George Welsh. This guy was a winner and nothing was going to stop him.

“If you accept limits on what you can accomplish then you don’t belong in coaching,” he said. “And if you don’t think you can reach the top you’ll never get there.”

The fact that his staff had recruited the state of Virginia helped. They knew the territory, the high school coaches. Still, it would take time to even get the better players in the state to consider taking a visit.

One thing that greatly disturbed Welsh when he opened up spring practice in ‘82 was the response he was getting from his players.

“We weren’t going to get it turned around if the players didn’t buy into our program and I don’t think they bought into it the first year,” Welsh said. “The first spring practice and the first [August] training camp practices were horrible. When I went to Navy it wasn’t like that. When I got here, they didn’t want to hit, they didn’t want to work. We never did get it done that year.”

Virginia went 2-9 that first season, 1-5 in the ACC.

“We could have had a few more wins that season,” Welsh said. “When we opened with Navy (a 20-16 loss), a lot of our kids were hurt, but we almost made it. We almost got to the point where we could beat Navy. But when we lost that game I think a lot of those kids — maybe they had been losing too much — lost confidence.”

The Cavaliers would lose their first five games to Navy, James Madison, Duke, N.C. State, and Clemson, before they finally broke through with back-to-back wins over Wake Forest and VMI. Then they dropped their last four to Georgia Tech, North Carolina, Maryland and Virginia Tech.

“I think some of the juniors on that team really helped us when they became seniors the next season,” Welsh said. “They gave us leadership, like a Billy Smith for instance.

“Whatever we wanted them to do, they were willing to do it,” Welsh said. “If we had asked them to practice four hours, I think they would have done it. In the process we got tougher physically and mentally.”

Welsh had some talent in Jim Dombrowski (eventually College Football Hall of Fame offensive tackled), quarterback Wayne Schuchts, lineman Bob Olderman, back/receiver Quentin Walker. The defense didn’t come around until the third year.

“If you could say one thing, it was that we finally convinced them that this was the way we were going to do it, and they bought into it,” Welsh said.

That was crucial, to turn the attitude around. But it would require much more to get Virginia off the schnide.

Recruiting had to change and Welsh knew it.

“You’re a state school and if you can’t do it in your state, you’ve got problems,” the UVa coach said. “You can’t get them all in your state, but if you get two or three. You’re better off getting the bulk of your team from within a five- or six-hour drive.”

Welsh knew what had to be done to rebuild the Wahoos. He had learned a lot of football while serving as an assistant coach at Penn State under Rip Engle and Joe Paterno.

He learned that you play like you practice and practices were hard, often grueling. He took that approach to Navy, and so he knew the blueprint would work at Virginia.

It’s what he labeled “Virginia Football,” built with a physical, power running attack and a physical defense in the mold of Penn State.

“We didn’t have a lot of great wideouts at Penn State but we had big-time offensive linemen and lots of good running backs (Welsh coached Lydell Mitchell and recruited Franco Harris to Happy Valley),” Welsh said. “That’s how I learned it.”

Welsh believed that having a good head coach, but if you didn’t have the right staff and the chemistry to go along with it, it wouldn’t work. Welsh had both at Navy and UVa and kept that staff together for the most part for a long, long time.

The running game was his bread and butter, though.

“You have to be able to hang your hat on something,” Welsh said. “We had about four or five running plays at first, but evolved into passing plays. We had about 10 counters and 10 off-tackle plays.”

As Virginia began to add better players to its roster, things would evolve seasons later.

“Teams absolutely knew what we were going to do as far as the running game was concerned,” Welsh said. “We had quarterbacks who could throw the ball and we still had good wideouts as we moved along. Eventually, if [opponents] didn’t defend our passing game, we just killed them.”

COMING TUESDAY: PART 2