‘Hoos Making a Difference’ honors Copeland, a true difference-maker

By Jerry Ratcliffe

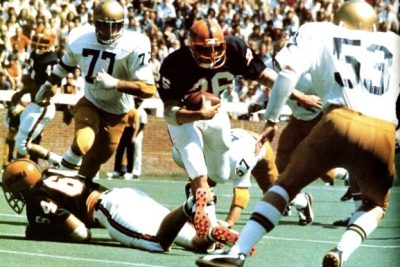

Bill Copeland doesn’t get around like he used to after a couple of back surgeries to repair some punishment he took as a running back in the mid-1970s, so he may require a little assistance.

Bill Copeland doesn’t get around like he used to after a couple of back surgeries to repair some punishment he took as a running back in the mid-1970s, so he may require a little assistance.

Still, living only four blocks from his alma mater’s famed Rotunda, when he’s able to walk the hallowed Grounds, it is a sweet and nostalgic time, conjuring up all kinds of memories of growing up in Charlottesville.

Once a small, quiet town, his hometown has changed over the decades, a bittersweet reality for those who grew up here in the Baby Boom generation.

Copeland is a sample of that era that made this town special. A member of a solid family, he played football for legendary Tommy Theodose and Joe Bingler at Lane High School, then moved on to UVA, just like his older brother Jim had done.

Bill also became interested in education, which served him well when he became football coach and taught Bible at Stony Brook School in Long Island, N.Y., prior to returning home to become headmaster at Covenant School. After several years back in Charlottesville, Stony Brook lured him back as its headmaster.

Charlottesville beckoned again, when he was called back to become pastor at Christ Community Church, an urban church with a diversified congregation, something he helped build into a success for more than a decade, having retired not long ago.

This past Saturday, light years from wearing a Virginia football uniform, Copeland was honored by the UVA Football Alumni Club’s “Hoos Making a Difference” program, which highlights former players or those who have been associated with Virginia football, who went on to serve a greater good.

Certainly, Copeland fits that description, having impacted thousands of lives in education and religion. To be honored by his fellow football brothers and to be recognized for his decades of good deeds produced a special moment for him, his wife, Sherry, and their family.

“I was shocked and humbled,” Copeland said about getting the honor. “I guess when you get to age 67 and you kind of think, ‘Wow, that was a long time ago,’ so I’m proud.

“That they are acknowledging that I did something well for the University of Virginia, that’s special. Being able to invest back into the community here and make some positive changes, I’m so glad I had those opportunities.”

It had been a long time since Copeland had visited the end zone at Scott Stadium, and so memories began flowing a few nights before Saturday’s ceremony.

“I was sitting in my chair, and I had this nervous feeling, just a strange feeling, thinking it was kind of like a pregame feeling when I played,” Copeland chuckled. “You know, the stuff you would go through on a Friday night before games. And I thought to myself, ‘Wait a minute, I’m 67. I’m too old for this.’”

His nerves were under control Saturday, when he looked up from the end zone and viewed photos of his game days in a Cavalier uniform.

Copeland cut his teeth on football playing for Lane, a football powerhouse in those days, and was good enough to attract several football scholarship offers. Lou Holtz, then the head coach at NC State, almost convinced Copeland to join the Wolfpack. In the end, he chose UVA over State and Virginia Tech.

His football career started well at Virginia, rushing for 700 yards as a freshman for Don Lawrence’s 1973 Cavaliers, good enough to finish in the ACC’s top 10 rushing totals that year.

Lawrence was dismissed after that season and Copeland ended his career a few years later having played for three head coaches in four years — Lawrence, Sonny Randle (two seasons) and Dick Bestwick. Still, in 1975, he posted four rushing touchdowns, also top 10 in the ACC that season.

“That ‘73 season, we had a really good offensive line and we ran a system that kind of fit my style of running, very similar to what I had in high school,” Copeland said. “Sonny brought in more of a pro-style type of offense and by the time Bestwick got here, it was my third different system in four years. So, yeah, it was hard.”

While learning the systems was challenging, it was more difficult adjusting to the personalities of the three head coaches.

“You either agreed or disagreed with three very distinct, different personalities that you had to transition to,” Copeland remembered. “You know, as a player, you want to please your head coach. That was the hardest part.”

Copeland did his best, relying on lessons learned at Lane, where Theodose and Bingler were turning out a surprisingly high number of college football players for such a small school, but also turning out more players with character, who would be credits to their community.

“If you were going to play for those men, you were going to play to the best of your ability, and you were going to play as a team,” Copeland said. “I look back on those years and am so thankful to have those men in my life, at a key time, a key age.

“I still see a lot of the guys I played with and we all agree how fortunate we were to have played for those men. They cared about us as people. We were a good football team and they cared about us as football players, but even more so as people.”

Copeland channeled a great learning moment under Theodose, a lesson he never forgot.

“One day in a classroom I did something that upset one of the teachers and she went down and told Coach Theodose. When I went down to gym class, Coach told me told me to come into his office, and boy, did he let me have it. He said, ‘We do not act like that, and I never want to hear this again.’

“One day in a classroom I did something that upset one of the teachers and she went down and told Coach Theodose. When I went down to gym class, Coach told me told me to come into his office, and boy, did he let me have it. He said, ‘We do not act like that, and I never want to hear this again.’

“I got the message. And over the years (as a coach, educator and pastor), when I had to deal with a young person, I often thought about how Coach Theodose would handle the situation. People like that stick with you through your life.”

When it came time to choose a college, it would have been natural for Bill to follow in his brother Jim’s footsteps. Jim was an outstanding lineman at UVA, went on to play professionally for the Cleveland Browns, then got into athletic administration, working for the Virginia Athletics Foundation, eventually becoming athletic director at Utah, back to UVA, and then to SMU, before returning to Charlottesville and passing away after a long fight with cancer.

“I didn’t want to necessarily follow my brother’s footsteps,” Copeland said. “I love my brother and respected him, but I wanted to have my own life.”

As mentioned, he came close to committing to NC State — “Lou Holtz could charm anyone,” Copeland said — but eventually stayed home to play for the Wahoos.

While UVA didn’t win a lot of games during his stay, he still had great memories, more about people than games.

“My favorite memory is the type of players, men, that I got to play alongside,” Copeland said. “As I look back on my days at UVA, the depth and the quality of the guys who were teammates, not necessarily football-wise, but in general, was really wonderful.

“So many of them have gone on to do well in life. No matter how bad things got on the field, I could look around that locker room and say, these are quality men that I’m with and I’m thankful to be able to say that.”

The “Hoos Making a Difference” recognition is all about honoring such players, those who have made the UVA football program and their communities proud of what they went on to achieve in life.

Bill Copeland has truly made a difference in the fabric of Charlottesville.