Let’s Take The Way Back Machine Way Back…To Nov. 20, 1941

Welcome to another adventure in “Hootie’s Way Back Machine,” where we travel back into Wahoo history and detail a significant moment.

Today, we’re going way, way back to Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 20, 1941, to Kenan Stadium in Chapel Hill, N.C.

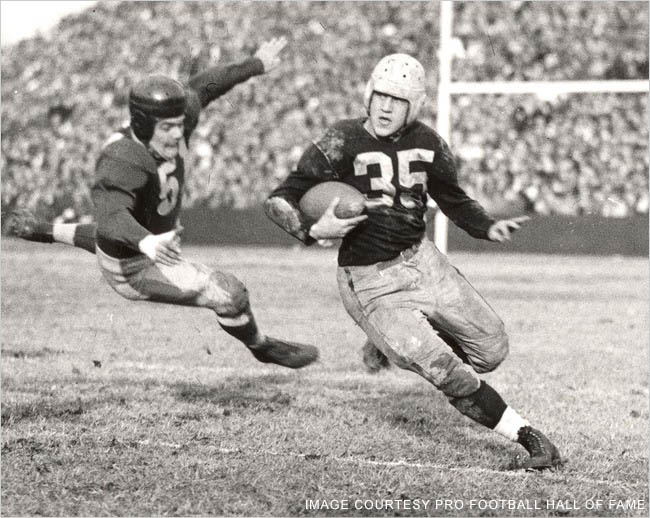

It was the final game for legendary Virginia star Bill Dudley, known in these parts as simply the “Bluefield Bullet,” or just the “Bullet.”

Was customary in those days for UVa and North Carolina to play a traditional Thanksgiving Day between the South’s Oldest Rivalry, which remains the oldest to this day. This particular matchup was huge, because it was Dudley’s last game as a collegian.

Runner-up for the Heisman Trophy and winner of the national player of the year awards by the Philadelphia Maxwell Memorial Club, and the Washington Touchdown Club’s Walter Camp Memorial Trophy, Dudley led the nation in scoring (134 points) and total offense (1,824 yards), although college football did not include receiving yardage and punt returns in totals during those days.

Overlooked was the fact that Dudley was also UVa’s best defensive back on a squad that allowed only 42 points all season.

Making the Bullet’s feats even more impressive was the fact he was only 19 years old. He entered UVa as a 150-pound, 16-year-old in 1938.

He would become the youngest All-American in the history of the Associated Press All-America team.

Considering all his accomplishments during his stellar career, nothing compared to the way he finished. Virginia had not beaten rival UNC in nine years and Dudley was determined to end that streak in his finale.

Speaking about that game, the Bullet once told me this story:

“We stayed at the Carolina Inn there in Chapel Hill (it’s still there), and when we woke up on game day, someone had slipped little cards under our doors,” Dudley said. “The cards read: Nine Long Years.”

Dudley never discovered who passed out the cards but he got the message. In fact, he was so fired up over breakfast and on the team’s bus trip to the stadium that UVa coach Frank Murray couldn’t help but notice that his star back might have been too intense.

Murray instructed quarterback John Neff to not give the ball to Dudley for the first few plays so that the back could calm down and settle in.

Normally Dudley would get the first carry off tackle or a quick opener, and he was a bit miffed that he wasn’t getting the ball and confronted Neff in the huddle.

Neff responded: “Well, I guess you’re settled down now.”

North Carolina would have preferred that Dudley kept his hands off the pigskin, because this is what the Cavalier star went on to do in UVa’s 28-7 win over the Tar Heels:

- Passed 16 yards to left end Bill Preston, who ran for five more yards and the Wahoos’ first touchdown in the first quarter.

- Dudley circled left end later in the quarter and jetted 67 yards for the second TD.

- In the third quarter, Dudley ran from semi-punt formation, sweeping to the right side and cutting back to take it to the house on a 79-yard scoring run.

- Passed again to Preston in the fourth quarter for 43 yards to set up the final TD of the game, which he scored himself from the 3-yard line.

For the day, Dudley scored three TDs, passed for the fourth, and oh, get this … he kicked all four extra points. He rushed for 215 yards on 17 attempts, completed 6-of-11 pass attempts for 118 more yards, and averaged 39.3 yards on eight punts.

I had the pleasure years ago of talking to one of the Tar Heels on that team, Harry Dunkle, who was UNCs captain. We talked at length about that game, and Dudley left an indelible impression on the Carolina player.

“I don’t know what kind of offense Virginia ran against us that season, but I would say it was something like the wishbone is now,” Dunkle said. “It was a diamond-type of setup with the quarterback lining up behind the center. We had never seen it before.

“The quarterback (Neff) handled the ball for handoffs and would also toss pitchouts to Dudley, but if they were going to pass, the center would snap the ball directly past the quarterback and to Dudley, who would throw it,” Dunkle remembered. “He was a good runner and he would kill us on those pitchouts to the left and right. As a linebacker, I remember the first time Dudley ran outside that day … I could see we were going to have a difficult day.”

Virginia’s offense was a “double wingback” version of his T-formation, schemed to take advantage of Dudley’s skill.

One of Dudley’s teammates from those days, Eddie Bryant from Culpeper, told me more about playing with the Bullet.

“Anything you had Dudley in the backfield, you were awesome,” said Bryant, the other halfback in that backfield. “It was great playing with Dudley because everyone was trying to stop him and that helped the rest of us.”

Bryant said Dudley was the best football player he ever saw, although he razzed his famous teammate by saying that Dudley was also the slowest back on the UVa team.

I remember passing that along to Dudley, who couldn’t help but laugh.

“I was very slow,” Dudley chuckled. “My best time in the 100 was about 11.2. I had a good start. For 40 yards, I could keep up with anybody. In fact, I could lead a lot of people at 40 yards. After that, I kind of wore down.”

His speed, or lack of it, didn’t discourage NFL teams. Dudley was the No. 1 draft choice of the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1942, and went on to lead the league in rushing, winning NFL Rookie of the Year and All-Pro honors for that season.

After serving as a B-29 Bomber pilot in WW2 in the Pacific Theatre, Dudley was the NFL’s MVP in 1946, was traded to the Detroit Lions where he was All-Pro twice between 1947 and 1949, and was eventually inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton in 1966.