The Herman Moore Story You Didn’t Know

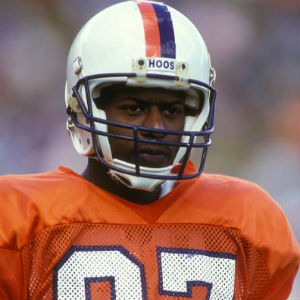

I well remember the recruiting war primarily between Virginia and Virginia Tech for Herman Moore, a budding wide receiver prospect from George Washington High School in Danville.

Moore had committed to Tech but UVA convinced him to come to Charlottesville for a visit, then convinced him to stay. Needless to say, that didn’t go over well in Blacksburg.

From that point on, I always thought I knew the whole Herman Moore story. Record-breaking wide receiver at Virginia, the other end of the fabled “Moore to Moore” pass combination with quarterback Shawn Moore. Then on to NFL stardom with the Detroit Lions. Pro Bowls, franchise records, NFL records. Mentioned in the same breath as Jerry Rice for goodness sakes.

I thought I knew everything about Herman. I was wrong.

Last Sunday night, Moore made a whistle-stop in Charlottesville to deliver an inspirational speech to Central Virginia high school football players at the 64th Annual Falcon Club banquet. Club president Jimmy French picked a winner to reach all the youngsters in attendance (we will recognize some of them later in the story).

I had always been under the impression that college scouts knew about Moore all along. They didn’t.

He played football from his peewee days at six years old when he quit the team because he was the smallest guy on the squad, all the way to high school without much success. He learned valuable lessons along the way, something he calls his journey.

That day he pulled off his pads and pouted at practice, told the coach he was quitting, turned out to be a good day. His mother happened by and told him he wasn’t quitting, that you don’t quit something you’ve started.

“That proved to be one of the best messages ever,” Moore told the audience. “I said, momma, I promise I’ll never quit again.”

His football career continued in obscurity. He never got into a game throughout those years, not until the 11th grade when a cornerback got hurt, and Moore, a wide receiver, was sent in. He made a few tackles but not much of an impression on his coaches.

Once he became a senior at GW, he blossomed but not in the way one might think. He was the team’s kicker, and still holds the GW record for the longest field goal (48 yards). He was a better basketball player and a better track and field performer, having high jumped over seven foot. In football, eh…

He was a backup tight end and a backup flanker. Because he didn’t see a future in athletics, he wasn’t a good student either. He wasn’t prepared for life after high school.

Everything changed abruptly in his last high school football game of his senior year when Danville was playing Albemarle High School in Charlottesville. Tom Sherman, an assistant on George Welsh’s Virginia football team, was at the game to watch his son, Tim, who was Albemarle’s quarterback.

GW was leading at the end of the game and Albemarle’s only chance was for the younger Sherman to throw up a “Hail Mary.” Because of Moore’s leaping ability, GW’s coach sent him in and told him to just jump up above everyone else and knock the ball down.

Well, Herman was standing there in the end zone, saw the pass coming, began his leap toward the ball and thought to himself, heck, I’m going to just catch it. He did, making the interception.

Immediately after the game, Coach Sherman visited the GW locker room and inquired, “Who’s that No. 82?”

GW’s coach said, “well, he’s a pretty good kicker.”

Sherman knew better. He recognized that No. 82 could do two things. One, he could really jump. Two, he could catch.

Moore’s life changed in an instant.

Virginia offered and as soon as that happened, everybody wanted Herman Moore.

He committed to Tech, was pressured into visiting Virginia, where he hooked up with Shawn Moore. It was a football marriage made in heaven.

Moore signed with Virginia but he wasn’t ready academically and had to spend the entire summer trying to catch up and become eligible. He got his break at UVa when Tim Finkleston was injured and Moore was sent in as a replacement.

He ended up becoming the No. 1 receiver in college football at that time, was sixth in the Heisman Trophy race and was a first-round draft choice of the Lions, where he went on to rewrite the record books.

Things weren’t always rosy at Virginia. He and Welsh often collided, at least during Moore’s first few years.

“I came close to leaving the Virginia program because Coach Welsh and I would argue all the time when I was younger,” Moore said. “When you’re young, you get caught in your own way and not realizing what’s good for you. I give Coach Welsh credit that he didn’t give up on me.”

There was a day in practice when Shawn Moore threw a pass to Herman, and the ball was tipped at the line. Herman watched the ball go incomplete and walked past the ball on his way back up the field.

Welsh barked at Herman to bring the ball back with him. Moore picked it up and threw it back, drawing the ire of Welsh.

“He said, don’t throw it back, I want you to run it back,” Herman recalled. “I walked it back, being stubborn. It’s almost embarrassing to say. I walked it back and he said: ‘Just leave. Get off the field, you’re done. Get off the team.’”

Moore, being stubborn answered, “so what, I’ll leave,” and walked off the field.

Understanding the error of his ways, Moore circled back later that afternoon and apologized, and Welsh accepted him back on the team.

“I would have never achieve what I did if I had let that moment go,” Moore said. “Again, it’s recognizing opportunity.”

It was also a promise to his momma that he would never quit.

Same thing happened in his rookie camp with Detroit. He dropped the first three passes from Andre Ware in his first preseason game. Here’s a first-round receiver who couldn’t catch a simple three-yard route. Some 60,000 fans were booing him.

He almost quit. Whether it was embarrassment, a lack of confidence, it was testing him to the point where he wanted to give up. But he didn’t. He didn’t quit.

He worked harder and better prepared. He became the fastest player in NFL history to reach 600 receptions, was the No. 1 receiver in the NFL.

Moore told the audience that football has a shelf life.

“How do you understand what to do in crisis? You lose a lot of days but you can go out and correct what’s wrong on the football field. Why can’t we do that in life?” Moore challenged them. “Whatever you do, give it your best. Don’t be afraid to fail. Always be prepared for what’s next.”

“You have to prepare for opportunity,” Moore said. “You don’t know when it’s going to come and where it’s going to come from, but are you ready to receive it?

“A lot of us go out and say we want to do all these things, but quite often we don’t know if we’re really prepared for it,” he added. “You don’t want to miss opportunities because of that. That came close to home for me from high school to college and from college to the NFL.”

Here is a list of the major award winners at the Falcon Club event:

The Most Valuable Player award, named after C.D. “Chubby” Proffitt, Jr., went to Louisa’s Brandon Smith (public school), and to Woodberry’s DeQuece Carter (private school). Smith was unable to receive the award because he is an early enrollee as a linebacker at Penn State.

Smith also won the Joe Bingler Defensive Player of the Year award.

Coach Jesse Lohr of Orange accepted the Carl Dean Sportsmanship Award for his program.

The Darden and Jim Towe Memorial Citizenship Award was presented to Jamie Edwards of William Monroe, while the Gene Brown Leadership Award went to Joshua Elliott of Fluvanna.

The Harry Martin Memorial Trophy for outstanding public school coach went to Mike Morris of Fluvanna, while the Walter Bickers Trophy for outstanding private school coach was presented to Covenant’s Seth Wilson.

Each school present awarded a team MVP trophy to one of its players. Here’s the list:

Albemarle-Eric Taylor; Blue Ridge-Xavier Kane; Charlottesville-Sabias Folley; Covenant-Jonas Sanker; Fluvanna-Prophett Harris; Fork Union Military-Larry Elder; Louisa-Brandon Smith; Monticello-Malachi Fields; Orange-Jaylen Alexander; St. Anne’s-Belfield-Thomas Harry; Western Albemarle-Aidan Sanders; William Monroe-Jame Edwards; Woodberry-DeQuece Carter.