The Real Story Behind ‘Ralph’s House’

By Jerry Ratcliffe

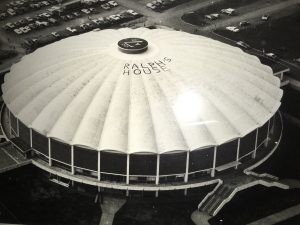

Photo courtesy Tommy Hicks

“Ralph’s House.”

What started as a simple, after-dinner chat about how to leave their mark on their college days 40 years ago, evolved into an everlasting phrase in Virginia basketball lore for a small group of UVA students.

It was the wee hours of April 13, 1979, when Cavaliers’ basketball player Tommy Hicks and two cohorts, Rusty Cleveland and Bobby Edwards, snuck onto the roof of University Hall, armed with 35 cans of black spray paint to emblazon the basketball arena with the immortal words: “Ralph’s House.”

Their secret mission was to make the nation’s No. 1 basketball recruit, the 18-year-old phenom of over the mountain in Harrisonburg, feel more than welcome on his official visit to UVA, and perhaps help sway him away from suitors Kentucky and North Carolina.

At the time, Sampson wasn’t overly impressed as the UVA coaching staff arranged for the 7-foot-4 center, to fly over campus in a helicopter, highlighted at the end by a bird’s eye view of “Ralph’s House.”

Sampson said that he had been to Virginia several times for basketball games, had won two state championships in the building while playing for Harrisonburg High School, and didn’t really need to visit the school. However, Terry Holland and staff insisted that Sampson take an official visit, perhaps fearing that visits to Chapel Hill and Lexington, Ky., might sway him out of state.

UVA showed up in Harrisonburg in a van, brought Sampson to Charlottesville and to the parking lot at UHall, where the big man spotted a helicopter. He wasn’t keen on flying and wanted no part of a ‘copter ride. Again, UVA’s coaches persuaded him to agree and the ride was highlighted at the end with the flyover the arena with his name boldly shouting skyward.

“I thought to myself, ‘OK, they’re rolling out the red carpet and trying to influence me to come to UVA,’” Sampson said of his aerial view. “Honestly, I wasn’t really that impressed at the time.”

Forty years later, though, Sampson, now a member of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, looks upon that day with warmth.

“It means so much to me now,” Sampson said. “Looking back on it, it is one of my favorite memories from my days at Virginia.”

Had Hicks & Co. known that at the time, perhaps they wouldn’t have gone so far out of their way to attempt to influence the big-time player to come to Charlottesville. At the time, though, it seemed like the only right thing to do.

“We were having dinner at Landon and Bessie Birckhead’s home, where I lived in their basement for a couple of years,” said Hicks, a senior on UVA’s basketball team at the time. “I had moved to near Scott Stadium, but we were all having dinner at the Birckhead’s one evening and trying to figure out how to make our mark and do something fun and prankish.

“We knew that Ralph was coming in and about the helicopter ride, so we just came up with this idea to climb up and paint the sign and started the ball rollin,’”

Hicks chuckled that because Landon Birckhead — whose son, Frank, had been a loyal team manager — had “deep pockets,” Landon purchased the spray paint. Birckhead was one of the major supporters of UVA basketball at the time, and certainly knew the value of what Sampson would bring to the Cavaliers’ program.

“Because I had access to UHall anytime I wanted, I snuck up one day and checked out the press box on the west side of the building,” Hicks divulged this week about his casing the joint. “There was a lock on it, so we had to figure a way to get rid of that. Beyond that, there was no ability to do a dry run. At that point, it was pretty much just, ‘Go for it.’”

The threesome pounded a beer at their apartment around 2:30 a.m., packed up the 35 cans of spray paint in backpacks, drove to an apartment complex on Barracks Road across the football field adjacent to UHall, parked and walked to the arena.

Hicks said when they approached the door, it was wide open, which made them suspicious. Did someone know they were coming? Was this a trap? They tossed some rocks toward the door, made some noise to see if anyone came out from hiding, but there was no response, so they walked in. The arena was well lit with security lights on inside.

“We went up to the press box, we cut the bolt that the lock was attached to because that was easier than cutting the lock, and then we started across the catwalk (which stretched clear across the top of the arena),” Hicks explained. “We had never done that before, so we didn’t know what that would entail. It kind of threw us a curve because of the way it moved and swayed.”

After making it across, they went through a compartment that housed equipment that controlled the scoreboard, and right at the top was a “submarine-like” door that wasn’t locked, much to their delight.

“We pushed it open and out we went,” Hicks chuckled.

The tip top of UHall was sort of a round turret, he estimated maybe 12 feet in diameter, and two feet high.

“It was like people popping out of a submarine,” Hicks remembered. “Having not been up there before, it was pretty flat on top, then started sloping off. In the middle of all this, one of the funnier parts of the night was that a can of spray paint fell out of one of the backpacks and started rolling down the side of the roof. Rusty went after it, but let it go after it started going down the slope. It rattled all the way down and made a noise when it hit the gravel below.”

Oddly and perhaps untimely, a night security car came by but didn’t hear the noise and kept on going. Still, the three scurried about into hiding just in case.

“We got back to business, painted our letters and started back down,” Hicks said, unable to contain his giddiness from the evening’s hijinx. “By the time we left the building, we were completely on a total natural high. It was so much fun.

“By then it was about 5:30 in the morning, and of course we pounded another beer. In the same breath, we called the newspaper and told them to check out what was on top of UHall. When Ralph came in from Harrisonburg, we knew he would see it. I don’t think it changed history, but I think it was pretty cool to see for an 18-year-old prospect.”

While it has been decades since, Hicks had forgotten that at the time he had somehow dropped his meal card, leaving evidence of the culprits behind.

“I don’t know if anyone found it and turned it in and [then-athletic director] Gene Corrigan just squashed it or not,” Hicks said.

Hicks said a number of things could have gone wrong, but no one got hurt, and Virginia got Ralph, who rewrote Cavalier basketball history. Because it was a perfect April night, plenty of moonlight, no wind, a perfect view of the city, it was serene.

“Ralph’s House” became the rage of Wahoo Nation. Everyone was enamored with Hicks & Company’s fine work. Well, everyone except for some folks in Chapel Hill.

“Initially, what I heard was it hit the papers in Chapel Hill and they were just pissed off,” said Hicks, a longtime investment banker, who has lived in Utah for the past 39 years.

The name has stuck to University Hall to this day. The arena, which opened in 1965 and was used as UVA’s basketball home until the end of the 2005-06 season, is set for implosion on Saturday at 10 a.m.

Sampson, who organized some social events surrounding the demolition (he will push the button to detonate the explosives and bring Ralph’s House to the ground), said, “It’s like a death in the family.”

For Hicks, Cleveland, Edwards, and the Birckhead family, it was a well-kept secret for years, decades even.

“Nobody knew who did it for the longest time,” Hicks said. “We were pretty hush-hush about it because of the implications of defaming a piece of property.”

There are folks still around today who knew who the “culprits” were and still refuse to disclose their identities, although Hicks spilled all the beans in this article.

“It’s amazing that eight or so people sitting around a dinner table thinking of things to do came up with that [one amazing] idea,” Hicks concluded. “Once the suggestion of ‘Ralph’s House’ came up, it made a lot of sense.”

Perfect sense for a perfect time in Wahoo basketball history.

Ralph’s House.

We will never forget.