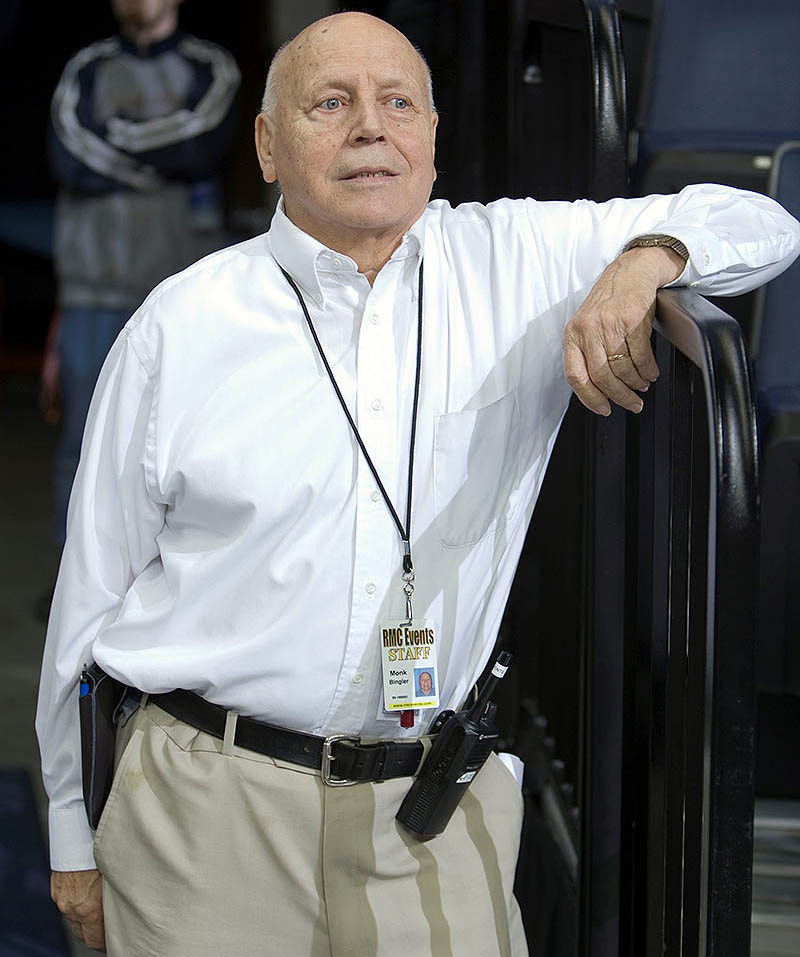

There Will Never Be Another Like James Thomas “Monk” Bingler

We knew him simply as “Monk,” the man at the door of Scott Stadium’s press box and various spots around John Paul Jones Arena. Year after year, Monk was always there with a handshake, a ready smile, a twinkle in his eyes, and usually a really corny joke.

James Thomas “Monk” Bingler, a Charlottesville legend, a University of Virginia “ambassador,” left us this week at the age of 94.

Most media that walked through the double doors to the press box each autumn had no idea of Monk’s background. He must have told me a jillion times that he had worked at UVa for more than 80 years, starting as an 11-year-old selling water at special events, then an usher. He was so proud of his history with Virginia athletics.

For years, he would meet game officials for basketball (Monk had once been a ref himself), at U-Hall or JPJ, and escort them to their dressing room and see them off safely at game’s end. He became a fixture in that respect, just as he did at welcoming media to the Scott Stadium press box.

One of Monk’s traditional greetings to any newcomer was this:

“Have you seen my pride and joy?” Monk would ask the unsuspecting soul. Bingler would reach for his wallet, while the soon-to-be victim expected to see photographs of Monk’s grandchildren.

Instead, he would pull out two photos of cleaning products, Pride furniture wax, and Joy dishwashing liquid. Everyone would roar with laughter just because they knew Monk’s gag had worked once again.

Few knew his history or his kindness. Those who did regarded him as a hero of sorts.

I sat with him for the longest time in one of the press rooms as he told me his story.

A member of the 394th infantry regiment of the 29th infantry division, Bingler’s C Company was part of the D-Day invasion at Omaha Beach. They fought their way through northern France and Belgium into the Ardennes Forest.

Monk would often tear up while describing how cold it would be and in order to keep their Browning Automatic Rifles from freezing up, they would have to urinate on them. One night, to escape the snow on the ground, he and some fellow soldiers climbed into trees, tying themselves to the tree so they wouldn’t fall in their sleep.

There was always some debate as to whether or not that’s where “Monk” came from (short for monkey), or whether the nickname originated from his youth when he bit a teacher and escaped punishment by climbing into a tree.

Anyways, much to the surprise of Bingler and his fellow soldiers, they were awakened by a German command post setting up practically underneath them. But they remained undetected and the Germans eventually moved on.

Monk was one of several U.S. soldiers captured on Valentine’s Day, 1945, and sent to a German POW camp, where they were ordered to work on roads. Once the work was done, German soldiers lined up the Americans and began to gun them down. Bingler and a few others ran for the forest, and Monk, with bullets whizzing past him, escaped and eventually made it back to Allied lines.

They traveled by night and slept during the day, often in cemeteries along the way. He was eventually wounded (and later received a Purple Heart) by mortar fire outside Bastogne.

My memory isn’t clear about where and when one of Monk’s stories took place, but he told me that he prayed that if he made it out of that jam alive, he would stop smoking and do whatever the Lord wanted him to do.

Monk woke up in a hospital somewhere in France and because all the nurses resembled angels in all white that he said to one of them, “Thank you Lord for taking me to heaven.” He thought he had been killed until a nurse answered, “You ain’t dead, you’re in a hospital in France.”

Doctors told him he’d never walk again. They were wrong. He never smoked again and did do the Lord’s work the rest of his life as he and his late wife, Fredell, were some of the founding members of the Charlottesville-Albemarle Rescue Squad.

He also received a Battle of the Bulge medal.

Monk had several occupations during the rest of his lifetime, but the one he enjoyed most was his association with UVa athletics.

I only saw Monk mad once in all the years I knew him. He had been at a local neighborhood mom and pop store, and had left a significant amount of cash on the counter. Another customer swiped the cash and left while Monk and the storekeeper were distracted.

Monk was livid. It wasn’t the money, it was the dishonesty that bothered him so much.

“If the man had told me he needed the money that bad, I would have given it to him,” Monk said.

That was Monk. He’d literally give you the shirt off his back if it would help.

Part of the agreement though, would probably have included having to endure the “Pride and Joy” gag a few more times.

For those of us accustomed to his warm welcomes and bad jokes at Scott Stadium and JPJ all these years, we missed him over the past season. He wasn’t up to the task. We never got to say goodbye.

Monk was a good soul.