By Jerry Ratcliffe

One might wonder how to honor a man as successful as Ralph Sampson, whose mother Sarah’s house in Harrisonburg is filled with trophies, plaques, and memorabilia from an illustrious basketball career — but, more importantly, with her son’s degree from the University of Virginia.

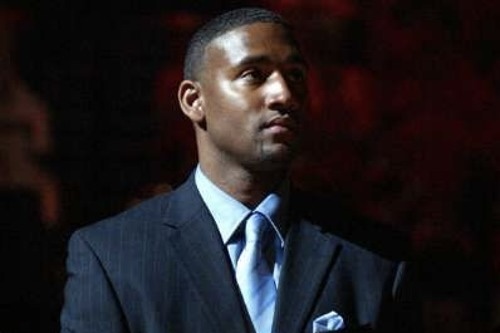

Sunday, on his mom’s birthday, with her in attendance, and also on the anniversary of Ralph’s official recruiting visit — yes, that one, when “Ralph’s House” was painted in big bold letters on the rooftop of University Hall — UVA paid tribute to Sampson’s career and lifelong contributions to the institution.

A gathering of some of his 400 closest friends, family, former teammates and coaches were regaled in colorful accounts of Sampson’s basketball deeds, including 3-time college National Player of the Year (Bill Walton was the only other to accomplish the feat), and both the Naismith and College Basketball Halls of Fame.

The school presented him a prestigious commemorative portrait of Ralph, by FM Morgan, with Sampson posing in his old room (No. 6) on The Lawn. It will hang forever in a special spot at the university.

More than a portrait was unveiled, as former teammates and admirers from as far back as Harrisonburg High School to UVA to the NBA shared stories of the big man’s greatness. When Sampson was inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame, none other than Magic Johnson, while presenting Ralph for the honor, described having never seen a big man with Sampson’s overall skill, that he was the NBA’s unicorn.

More than a portrait was unveiled, as former teammates and admirers from as far back as Harrisonburg High School to UVA to the NBA shared stories of the big man’s greatness. When Sampson was inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame, none other than Magic Johnson, while presenting Ralph for the honor, described having never seen a big man with Sampson’s overall skill, that he was the NBA’s unicorn.

Cory Alexander, who grew up idolizing Sampson and later played at UVA and in the NBA before becoming a TV hoops analyst, pointed out that during a recent game he was calling, his broadcast partner commented that basketball hasn’t seen a big man with the skill of present-day player Victor Wembanyama (San Antonio Spurs). Alexander knew better and reminded the audience that many might remember Ralph Sampson.

Marc Iavaroni, who played seven years in the NBA and later coached, credited Sampson for helping him take that step. Iavaroni had already left Virginia and had been playing professionally in Italy and was between careers. He was thinking about getting into coaching, returned to UVA where Coach Terry Holland asked him to practice against Sampson to toughen up the young phenom.

Sampson came to UVA with a 7-foot-4 frame, but weighed only 198 pounds, something that strength coach John Gamble (who was in attendance Sunday), quickly corrected, putting 17 pounds of pure muscle on the lanky big man by his sophomore season.

Sampson came to UVA with a 7-foot-4 frame, but weighed only 198 pounds, something that strength coach John Gamble (who was in attendance Sunday), quickly corrected, putting 17 pounds of pure muscle on the lanky big man by his sophomore season.

“I appreciate Iavaroni,” Sampson said. “He made me a better player. He beat me up every day.”

Iavaroni said that if Holland hadn’t come up with that idea and if Sampson hadn’t accepted him as a practice partner, Iavaroni would never have taken that next step to the NBA.

Iavaroni shared a couple of stories, noting that in his first pro game against Sampson (Houston Rockets) at the Spectrum against Iavaroni’s 76ers, Sampson dropped in 20 points, an average game for Ralph, who scored 21 points and 12 rebounds his rookie year when he was unanimously voted the NBA’s Rookie of the Year.

“But the next time we played Ralph was in Houston, and just to let you know what a quick learner Ralph was, he dropped 41 on us,” said Iavaroni, who was surrounded by a few Hall of Famers on Philadelphia’s roster.

“Thank God for YouTube,” Iavaroni said. “I look back and watched Ralph play and I mean, ‘you played hard, Ralph.’ Maybe it’s because I’m comparing it to the NBA of today, those guys making good money and providing a lot of entertainment, but it’s not even close to how hard Ralph played. People might not remember that, but go back and go on YouTube.

“A lot of people would have just relied on their talent, and Ralph never did. He brought it every single night and he brought it to every single practice at UVA.”

Wally Walker, who starred at Virginia prior to Sampson’s arrival, had already been in the NBA and won world championships prior to Ralph being the No. 1 draft pick by Houston. Walker was Ralph’s teammate on the Rockets that rookie year and wasn’t a fan of coach Bill Fitch, who didn’t play Walker much that season.

Wally Walker, who starred at Virginia prior to Sampson’s arrival, had already been in the NBA and won world championships prior to Ralph being the No. 1 draft pick by Houston. Walker was Ralph’s teammate on the Rockets that rookie year and wasn’t a fan of coach Bill Fitch, who didn’t play Walker much that season.

In fact, Walker and Sampson were in the starting Rockets lineup in Ralph’s debut. Walker went 7 for 10 shooting that night, he chuckles, about a month before Fitch “decided I should never play an NBA game again.”

“Because I wasn’t playing much, I had a great seat for 82 games, watching Ralph play,” Walker said. “The NBA wasn’t as popular or prosperous then as it is now, and I fear that people have forgotten a little bit. I’m glad Cory made reference to Wembanyama (and Sampson) because that’s the right comparison. I worry that people have forgotten how great this man (Sampson) was as an NBA player.”

Walker, who later became president and general manager of the Seattle SuperSonics, said he struggled to describe the pride he had when playing in the NBA and watching what Ralph did for Virginia basketball.

“To know that he had brought us to a place where we were in every conversation about being the best in the country was amazing,” Walker said. “Three-time national player of the year — that will never happen again.”

Iavaroni said he was often asked by NBA teammates about Sampson.

“In fact, I always got introduced as a role player, playing alongside four future Hall of Famers in Philadelphia, and every time I would score a point or started a game [the TV/radio announcers] would always say, ‘he worked with Ralph Sampson.’ I was like, well, you can’t get a better introduction than that.”

When he was hanging out with teammates on a road trip and they asked about Sampson, about practicing against him, Iavaroni always had a simplistic reply.

“I said, as good as he is as a player, he’s better as a person,” Iavaroni said.

Sampson was true to that on Sunday, recognizing practically everyone in the room, bringing up new UVA coach Ryan Odom, former women’s coach Debbie Ryan, former teammates Craig Robinson, Darren Cross, Ricky Stokes and Terry Gates, Ann Holland, recognizing John Gamble, Joe Gieck, sharing all his glory with those who meant so much to him in various stages of his story.

Sampson was true to that on Sunday, recognizing practically everyone in the room, bringing up new UVA coach Ryan Odom, former women’s coach Debbie Ryan, former teammates Craig Robinson, Darren Cross, Ricky Stokes and Terry Gates, Ann Holland, recognizing John Gamble, Joe Gieck, sharing all his glory with those who meant so much to him in various stages of his story.

He quoted his mom, who told him, ‘if you’re going to do something, it’s got to mean something.’

Surrounding himself with those dear to him for the portrait unveiling, Sampson capsulized his life when he called them up on stage.

“It’s not about me … it’s about we.”